How marketers lost faith in Facebook

- 11 April, 2014 03:34

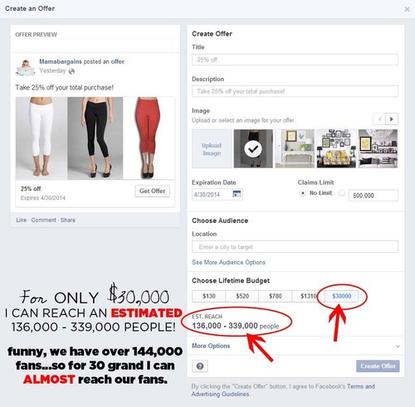

Mamabargains, a daily deals site, takes issue with the amount of money charged for promoting some posts.

In space, they say, no one can hear you scream. Some marketers feel the same way about Facebook.

The social network has come to play a vital role for many of the million-plus businesses that promote their brands and connect with customers on its site. But it's clear that some marketers no longer see Facebook as their friend.

A recent post on the site by Eat24, a food delivery service, was the latest sign of marketers' discontent. The problem, Eat24 and others say, is that Facebook's algorithms that determine which posts appear in users' News Feed are unpredictable, and they're increasingly weighted towards those who pay to promote their posts.

"We give you text posts, delicious food photos, coupons, restaurant recommendations ... and what do you do in return? You take them and you hide them from all our friends," Eat24 said in a "breakup letter" to Facebook.

"It makes us think all you care about is money," Eat24 wrote, and promptly deleted its account from Facebook.

The social network won't be crying over the loss of one customer, but it points to a larger challenge for the site: As more businesses advertise on Facebook, it has to find a way to display their posts in users' News Feeds, which often are already crammed with posts from hundreds of friends.

But it has to do so in a way that won't alienate people by making them feel bombarded by marketing. And it needs to strike the right balance with what most people join the site for in the first place -- to connect with their family and friends.

One of the main vehicles for companies to promote their products and services is Facebook Pages. For free, they can set up a page and try to get people to visit it, often by generating likes.

But it's not easy getting people to "like" your page. Some marketers do it unscrupulously, by paying "click farms" that hire thousands of people, often in developing countries, to click on their posts. Facebook prohibits that, and will punish businesses if it catches them doing it.

Another way is to pay Facebook to make posts appear higher in News Feeds, or to promote Pages with advertisements. Many businesses do that, but it's an area where discontent is brewing. Marketers say the likes generated through those programs aren't as valuable as in the past, because Facebook's algorithms have dialled down the visibility of their Pages.

Some see it as a bait-and-switch tactic. It's like selling a billboard under the premise that a certain number of people will see it, and then parking a bus in front of it, said Jessica Canty, owner of Jake's Coffee and Espresso in Staunton, Illinois.

Canty has paid Facebook upwards of $600 to advertise the shop's page and get more likes. For a while it worked, she said. But in the last couple of months views of her posts have dropped, even though the number of people who "like" the coffee shop has stayed roughly the same.

One day last week, a post advertising daily specials, like its sticky bun latte, received just over 200 views. A year ago, Canty said, posts were getting more than 600 views.

"Facebook is not nearly as useful as it used to be," she said.

Mamabargains, a daily deals site for parents and children, spent nearly US$60,000 on Facebook advertising last year, but that had almost no effect on the reach of its posts, said CEO Jessica Kurtz. Mamabargain's Facebook page has nearly 145,000 likes, which in good times could have ensured strong visibility for its posts. But recently, Facebook wanted Kurtz to pay $30,000 for her posts to reach an "estimated" 136,000 to 339,000 people.

"That's asinine," she said. If Mamabargains already has 145,000 followers, she wants to know, why should it pay all that money for its posts to be seen by potentially less people? Despite the strong following, she said, an average post today is seen by only 3,000 people.

Kurtz said she fields a constant stream of complaints from followers who don't understand why they no longer see Mamabargains' posts in their News Feeds. "I could hire someone just to handle our customer service complaints related to Facebook," she said.

Trying to adapt her posts to Facebook's constantly changing algorithms is also frustrating, Kurtz said. Sometimes adding a link provides more visibility, but sometimes it doesn't. Sometimes posts with photos work better, but sometimes not.

The company's sales have fallen by half in the past year, Kurtz said, and she holds the changes to Facebook's algorithms largely responsible.

Even if paying to promote a post generates more likes for a page, that might not help in the long run, said Josh Reiss, a photographer based in Los Angeles who uses Facebook to promote his work.

With so much content jostling to appear in people's News Feeds, having a lot of followers doesn't assure posts will be seen, he said. "So what if it gives you a few more fans? You still have to pay to promote future posts. You still fall back into obscurity."

Figures support the idea that the "organic reach" of marketers' posts -- the visibility they achieve without paying for it -- is falling. Social@Ogilvy, a marketing consultancy, analyzed more than 100 brand pages and found that organic reach hovered at 6 percent in February, down from nearly 50 percent in October. For large brands with more than 500,000 likes on their pages, organic reach in February was just 2 percent.

"Organic reach of the content brands publish in Facebook is destined to hit zero," the group predicted. "It's only a matter of time."

This leaves Facebook in a quandary. There's only so many posts it can show to users in a day, and it can't bombard them with marketing messages or they'll feel they're getting spammed. At the same time, it needs to show people the content they want to see, and in many cases that's not posts by marketers.

Brandon McCormick, director of communications at Facebook, said as much in a response to the post from Eat24.

"There is some serious stuff happening in the world and one of my best friends just had a baby and another one just took the best photo of his homemade cupcakes and what we have come to realize is people care about those things more than sushi porn," he wrote, referring to Eat24's food pictures.

Facebook isn't trying to punish businesses or decrease their visibility, McCormick said in an interview. It's goal is to increase the reach of posts that users have shown they like, by sharing or commenting on an item.

But he acknowledged that the reach of posts by businesses, unless they're paying to promote them, is declining. Marketers on the site can try to increase their visibility by creating more engaging content that will generate activity, like posts from people's friends do, he said.

Facebook offers some advanced tools, he noted, that marketers can use to target ads more effectively. Power Editor, for instance, let's advertisers try out dozens of variations on the same ad, and upload a database of customer contacts for better ad targeting.

Some of those tools appear more suited to larger businesses, however, and it's not clear they'll help to ease the frustration some marketers are feeling.

Some are already spending some of their marketing dollars elsewhere. Jake's Coffee and Espresso has started paying $35 a month to use Perka, a mobile loyalty platform, which sends messages to customers each morning.

Photographer Josh Reiss is looking at alternative ways to reach people. "I'm exploring more ways to connect with customers directly," he said.

"Brands are not going to abandon Facebook, but they will focus a larger portion of their marketing efforts elsewhere, for both organic and paid content," said Nate Elliott, a Forrester analyst who helps companies develop digital marketing strategies.

Part of the issue is that, much like Google with its search engine, marketers can't see inside Facebook's algorithms. They can adapt their content to try to get greater visibility, but ultimately they're subject to the whims of what Facebook decides. And when those decisions result in poor visibility for their brands, they're likely to feel they've been cheated.

"Marketers feel tricked," Elliott said.

Zach Miners covers social networking, search and general technology news for IDG News Service. Follow Zach on Twitter at @zachminers. Zach's e-mail address is zach_miners@idg.com